One of the largest clam beds in the world closed in 1990 because people could get sick and even die from eating clams contaminated with a deadly marine toxin.

This year, however, a large portion of the area called Georges Bank, 62 miles off the coast of New England, reopened after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed a new approach toward this risk to public health.

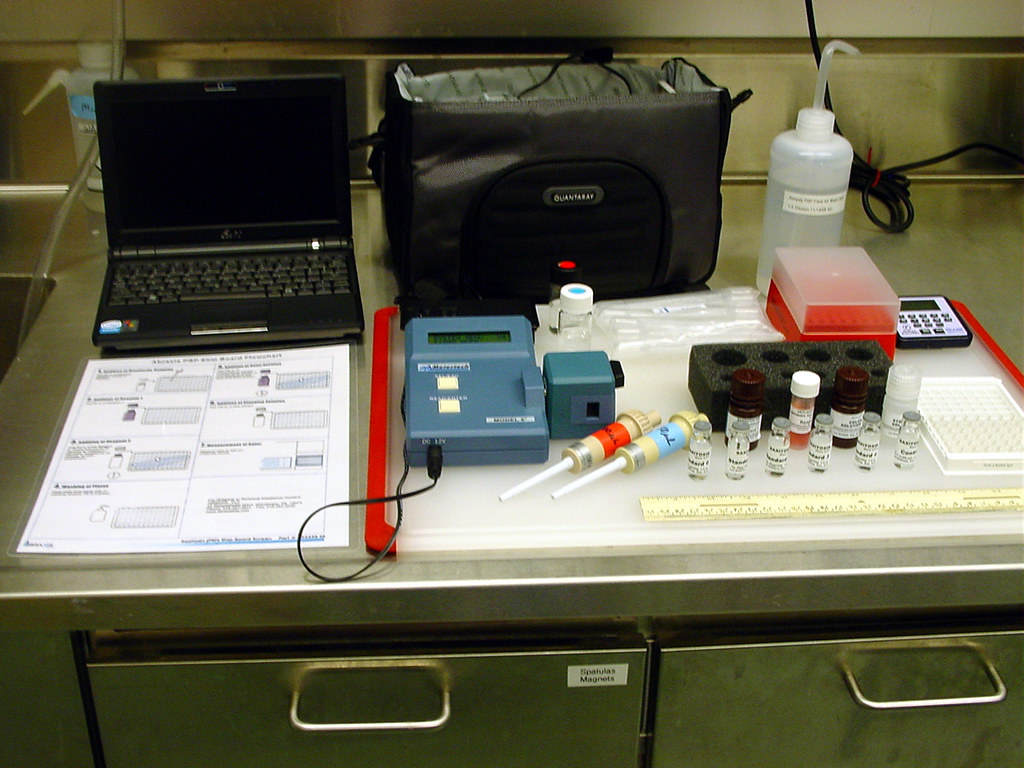

One major element involves having an FDA scientist train fishermen to perform sophisticated scientific tests on the clams while at sea, sometimes under extreme conditions.

"This program has almost doubled the number of quahog clams available on the market, and increases the availability of surf clams by about 40%," says David Wallace, a consultant for the seafood industry. "If it hadn't been for the FDA, these multi-billion dollar resources would be going to waste. It's good for fishermen, for consumers and for the economy." (The meat of quahog clams is tougher than surf clams and is often used in chowder, while surf clams often show up in raw bars.)

This is the story of how fishermen, industry representatives, state officials and multiple branches of the federal government worked together to create a novel plan that is allowing clams to be harvested from a major portion of Georges Bank—a vast submerged sandbank that extends from Massachusetts to Nova Scotia.

The story begins in the late 1980s, when harvest areas were temporarily closed due to the reports of toxins in surf clams from Georges Bank. After a brief reopening in early 1990, harvest areas were closed again when fishermen clamming on Georges Bank ate contaminated mussels caught while fishing for clams and became extremely ill.

The diagnosis: paralytic shellfish poisoning, caused by a toxin produced by Alexandrium algae. The toxic algae has been cited for centuries and is sometimes referred to as "red tide," even though not all red tides are toxic, and not all toxic blooms are red.

The toxin concentrates in the flesh of mollusks, including clams and mussels, and doesn't seem to hurt them. But in high enough concentrations, this potent toxin can temporarily paralyze humans. If this happens, the paralyzed person could die of asphyxiation if he or she is not put on life support until the toxins are flushed from the body. Cooking the mollusks does not neutralize the toxins.

The toxin concentrates in the flesh of mollusks, including clams and mussels, and doesn't seem to hurt them. But in high enough concentrations, this potent toxin can temporarily paralyze humans. If this happens, the paralyzed person could die of asphyxiation if he or she is not put on life support until the toxins are flushed from the body. Cooking the mollusks does not neutralize the toxins.

FDA officials, who are responsible for the safety of seafood caught in federal waters, could not put scientists on board every clam fishing vessel far out at sea to test the clams for the toxin. It didn't make economic sense for fishermen to spend the time and money harvesting clams if they might arrive at the harbor, discover they had a boat filled with toxic clams, and then be responsible for safely disposing of them.

The 1990 closure of Georges Bank was a huge blow to the clam industry. The situation became even more dire in 2005, when a massive algal bloom near the New England shores temporarily closed another 15,000 square miles of ocean to clamming.

The clam industry, finding itself in peril, decided to invest the time and money required to find a solution, and began working with state and federal officials. After years of research on a harvesting procedure that could deliver safe clams at the dock, followed by an intense, years-long research and a pilot program, a huge portion of Georges Bank reopened in 2013 to clam fishermen who agreed to work under a new FDA procedure. This includes having fishermen take the FDA-provided training needed to conduct very precise scientific tests of clam samples while out to sea.

"There was a lot of skepticism. How would the fishermen react to listening to days of lectures from a young government scientist? Could they accurately conduct tests that sometimes even challenge lab scientists?" says FDA marine biotoxin expert Stacey DeGrasse, who has provided the FDA training.

"The project, however, is incredibly successful. The fishermen take great pride in performing the on-board lab tests and provide exact, pristine data," says DeGrasse.

No comments:

Post a Comment